CHERRY HILL, N.J. (CBS) — It’s been 40 years since a

painting was stolen from a home in Cherry Hill and authorities are not

ready to give up on finding it.

The Cherry Hill Police Department is working in conjunction with the

FBI Art Crime Team to find the stolen Norman Rockwell painting. On the

anniversary of the theft, authorities are asking for the public’s help.

The FBI Art Crime Team was started back in 2004 to focus on art and cultural property crimes.

Officials say the painting was taken from a home on June 30, 1976.

The FBI says the piece of work in from 1919. Officials say it has a

few names including “Boy Asleep With Hoe,” Taking A Break,” and

“Lazybones.”

They describe the painting as oil on canvas. It’s dimensions are about 25 inches by 28.5 inches.

Anyone with information is asked to contact the FIB’s Philadelphia Division at 215-418-4000.

A Canoga Park man was arrested in connection with the theft of a

trailer containing $250,000 in artwork by Matisse and Chagall, police

said Tuesday.

Robert Michael Slayton was taken into custody Thursday on suspicion of grand theft, according to the

Los Angeles Police Department. He was released hours later on $70,000 bail.

Detectives found the stolen trailer in Slayton’s backyard in the

7700 block of Farralone Avenue in Canoga Park, police said. The trailer

was stripped.

Detectives from the Los Angeles Police Department’s Art Theft Detail recovered more than $120,000 in stolen art.

But not all of the stolen art has been recovered.

Los

Angeles police art investigators said the 24-foot-long, rectangular

2005 Haulmark trailer and roughly $250,000 in precious cargo

disappeared Nov. 20 from an industrial park in Chatsworth.

Two in court over alleged art theft from Billy Connolly’s former neighbours

Two people have appeared in court in connection with an alleged art theft from former neighbours of comedian Billy Connolly.

Valuable works by Scottish colourists George Leslie Hunter

and Francis Cadell were allegedly stolen from Candacraig Gardens in

Strathdon, near Connolly’s then home at Candacraig House, in 2001.

The two paintings are each believed to be worth a six-figure sum.

Penelope Hodge or Thomas-Smith, 60, and Philip Thomas-Smith,

66, appeared in private at Aberdeen Sheriff Court yesterday and faced a

charge of theft by housebreaking.

The pair, whose address was given in court papers as

Northern Cyprus, made no plea or declaration and were remanded in

custody pending the outcome of a bail appeal hearing.

Billy Connolly and his wife Pamela Stephenson bought Candacraig House in 1998 and had used it as a Highland retreat.

The 12-bedroom property, which was the former home of Body

Shop founder Anita Roddick, has hosted numerous famous stars including

the late Robin Williams, Steve Martin and Ewan McGregor.

The house features 12 bedrooms, 11 bathrooms, four reception rooms, a billiard room and library.

It is set in 14 acres of grounds, which include a walled garden, woodland and loch.

Amateur antiques dealer gets jail

An amateur antiques dealer has been jailed after he was caught with

57 stolen antique books, including an extremely rare King James Bible.

Andrew Shannon, aged 51, was previously jailed for damaging a €10m Monet painting at the National Gallery in December 2014.

Shannon, of Willans Way, Ongar, Dublin, pleaded not guilty at Dublin

Circuit Criminal Court to possession of the books at his home while

knowing or being reckless as to whether they were stolen on March 3,

2007. He was convicted by a jury last February.

Judge Petria McDonnell sentenced him to one year in prison with the final six months suspended.

Shannon was previously sentenced to six years imprisonment with

the final 15 months suspended for damaging the Claude Monet painting. He

had denied the charge but was convicted following trial. He moved to

appeal his conviction in December of last year but judgment is still

awaited.

Shannon’s 35 other convictions include theft and burglary.

The court heard that the 57 stolen books had originated in the

library of Carton House in Kildare, the historical family seat of the

FitzGerald family.

Detective Garda Des Breathnach told Maurice Coffey, prosecuting, that

in November 2006 the owner of Carton House reported that the books had

been stolen after they were put in storage during the restoration of the

country house.

The “distinctive books” were later found “openly on show” in the

house of Shannon in March 2007. Shannon was arrested in November of the

same year.

Counsel said the books were “an antique gem” and included a 1660

edition of the King James Bible. There was an agreement at the trial

that the total overall value of the books was €6,500.

Shannon told gardaí he purchased these books at a fete in the Midlands in 2002.

John Fitzgerald, defending, said his client suffered from a heart condition and asked the court to take this into account.

Judge McDonnell said that Shannon trained as a French polisher and

was an amateur antiques dealer who had a “propensity based on previous

convictions of acquiring things.”

A third 'Pink Panther' will stand trial in Dubai in connection

with the sensational heist where a gang stole Audi A8s, jewellery and

watches worth Dh14.7 million.

A member of a gang internationally known

as Pink Panther has gone on trial in the Dubai Court of First Instance

over the daring April 15, 2007, heist at a jewellery shop in Wafi Mall.

The 34-year-old Serbian, A.B., is the third 'Pink Panther' to stand trial in Dubai in connection with the sensational heist.

The group of armed robbers drove two stolen

Audi A8s through the glass façade at the mall before stopping at the

House of Graff and making their getaway with jewellery and watches worth

Dh14.7 million in front of stunned shoppers.

The Pink Panther gang is a loosely aligned network of criminals who targeted high-end jewellery stores between 1999 and 2015.

A.B. has committed many robberies in Europe,

including Monaco and Switzerland. He was arrested by the Spanish

authorities in February 2014 and handed over to the UAE authorities in

October 2015. Apart from the armed robbery charge, A.B. is also accused

of obtaining an entry permit with a forged passport and illegally

entering and exiting the country.

It was learnt that the defendant entered the

UAE with a forged Yugoslav passport on March 24, 2007, and exited on

April 17, 2007.

During that time, he stayed with a Bosnian

accomplice (a runaway) in a flat in Al Rafaa. The building watchman

identified them when he saw their photos.

A police lieutenant said: "We learnt that an

employee at a rental car office received an international call from one

of the gang members, telling him not to report to the police about the

car they had rented. He said they still needed it and promised to settle

the rent due on it."

It was a very useful tip for the Dubai Police.

They found the rented car about 500 metres away from A.B.'s flat. The

police watched the car until an Eastern European man (against whom no

charges were filed) went to drive it. He told the police it was rented

by one of the runaway suspects.

One of the gang members had earlier been

convicted by a Dubai court and sentenced to 10 years in jail for

arranging for the crime tools, including masks and gloves. Another

accomplice had been cleared of the charge of possessing a part of the

stolen items.

A police lieutenant said: "The Dubai Police

have been taking part in meetings held by the Interpol since the

robbery. On May 30, 2007, we took part in a meeting held in Germany and

submitted evidence picked up from the robbery scene, including DNA

traces of the suspects. The accused on trial was arrested by the

Interpol after those DNA traces matched with the samples saved in the

Interpol's database."

How the robbers became Pink Panthers

According to the defendant on trial, the gang

got its name based on a "true story" that took place in France a long

time ago. The gang stole a diamond from a jewellery exhibition and

smuggled it out of the airport in a cosmetic box. One of the gang

members was wearing pink clothes then.

Interesting facts about the case

> The Dh14.7 million Wafi Mall heist was carried out in less than a minute

> Dubai Police's investigation into the case helped Interpol identify the gang's modus operandi

> The heist car was put on show at the

Dubai Police Museum in 2013 to "reflect the police's ingenious work in

cracking the case"

> A 2013 film documentary called "Smash and

Grab: The Story of the Pink Panthers" chronicles some of the gang's

exploits and the efforts of law enforcement agencies - including Dubai

Police - to bring them to justice

> The gang is believed to have carried out

around 380 armed robberies targeting high-end jewellery stores between

1999 and 2015

> The combined value of the thefts is estimated to be over ?334 million

Once the world’s richest and most influential dealers, the family is trying to fight off a half-billion dollar tax bill.

Sources: The Met/Art Resource (5); The Art Institute of Chicago/Bridgeman Library

(Clockwise, from top left) Vincent Van Gogh’s Roses, 1890, donated by the Annenberg family to the Met in 1993. In 1951 the Wildensteins bought it for $100,000 and sold in 10 days later for $135,000; Michelangelo da Caravaggio’s The Lute Player,

circa 1597, long thought to be a second-rate copy. The Wildensteins

“discovered” it in their New York vault; Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s Ugolino and His Sons, 1867, which the Wildensteins sold to the Met in 1967; Pietro Lorenzetti’s The Crucifixion, circa 1340s. The Wildensteins sold it to the Met in 2002; Jean-August-Dominique Ingres’s Comtesse d’Haussonville, 1845, which the Wildensteins sold to the Frick Collection in 1927; Claude Monet’s Jean Monet on His Hobby Horse,

1872. The Wildensteins bought the painting from French-Jewish art

dealer Georges Bernheim in 1938, then sold it to a Standard Oil heiress

in 1943; Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Two Sisters, circa

1769-70, which the Wildensteins sold to the American coal magnate Edward

Berwind for $194,000 in 1918; Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day, 1877. The Wildensteins sold it to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1964.

Over

recent weeks in hushed New York dining rooms and private Parisian

salons, Guy Wildenstein has been a walking object lesson in how

billionaire dynasties decline: surrounded by lawyers, pitied, selling

off paintings—yet still fabulously rich. This is how it goes when you’re

facing a trial in an inheritance-tax case that could cost your clan

half a billion dollars. Or at least, what’s left of the clan: His

brother, father, and stepmother are dead. It falls to Wildenstein, 70,

to ensure the family’s fifth-generation art-dealing fortune makes it to

the sixth. Coming up with €448 million ($496 million) in cash—the amount

the French government claims his family owes in unpaid taxes and

fees—would be enough to bring even the world’s richest to the brink of

catastrophe.

Still, life must be lived. Wildenstein

parted with

$1.2 million worth of old masters at a Christie’s auction in New York

earlier this year, and he still has the Manhattan town house he bought

for $32.5 million at the end of 2008, though, according to recent press

reports, that’s

on the block,

too. In Paris, where the tax trial will be held, he has the family

apartment, though for now it’s been legally seized and the furnishings

are under seal. He still goes out in his double-breasted suits to mix

with the godfathers of French finance, drawing admiration for keeping up

appearances. They know it’s but for the grace of the feared

fisc—France’s equivalent of the U.S. Internal Revenue Service—that they

themselves aren’t explaining offshore trusts and Picassos in vaults to

the taxman. After all, Wildenstein is still one of them: the one who

sold his Gulfstream IV to then-Lazard Chairman Michel David-Weill back

in 2003; who banks with Rothschild, as his family has for decades; who

sustains the Wildenstein Institute, a temple to art history whose

catalogues raisonnés for

the most important artists of the 19th and 20th centuries are so

exhaustive that a work by Monet would be worthless without a so-called

Wildenstein index number.

“Nobody’s done as well as the

Wildensteins in terms of cash and power and, in a way most important of

all, respectability,” says art historian John Richardson. “Nobody.”

(l-r) Daniel, Guy, and Alec, photographed by Helmut Newton in 1999

“When

you were super rich and wanted to show off, you’d go to Wildenstein’s.

You could tell everyone back in Chicago, ‘Oh, I was in Wildenstein’s the

other day. I’m thinking of buying a Raphael.’”

Photographer: Helmut Newton/Maconochie Photography

The

family’s business runs on secrets—so fiercely kept that Wildenstein has

said he didn’t learn about the family’s financial machinations himself

until the death in 2001 of his father, Daniel. When it came time to

settle the estate, Guy and his brother, Alec, claimed their father had a

net worth of €40.9 million, or about $45 million. To cover the

resulting estate tax bill of €17.7 million, they gave the French

Republic—Nicolas Sarkozy, then president of France, was a close friend

of the family—a set of bas-reliefs by Marie Antoinette’s favorite

sculptor. Lovely as the reliefs were, this turned out to be a true

let-them-eat-cake moment, tossing crumbs to the French public while,

French prosecutors claimed, the Wildensteins were keeping a towering

confection of property, art, cash, and investments for themselves. In

the month of Daniel’s death alone, the government uncovered a veritable

airlift of art, with $188 million worth of paintings moved from the U.S.

to Switzerland.

One painting stayed where it was. A

Wildenstein-owned Caravaggio hung in a gallery at the Metropolitan

Museum of Art in New York. Known as

The Lute Player, it was

worth tens of millions of dollars, quite possibly more than the entire

declared estate. French prosecutors would soon conclude there had to be

more like it in the family vaults.

After making an appearance

before a judge one morning last January, Wildenstein lurked silently in a

corridor outside a criminal courtroom at the Palais de Justice, wrapped

in his tan overcoat. He stood behind a lawyer who did all the talking

about the unpleasant legal business, which is expected to culminate in a

trial later this year.

He had already told his story in the glossy Côte d’Azur beach read

Paris Match a

few months before. The last time a member of the insular Wildenstein

clan made use of the mass media was the first time most Americans heard

of the family: In the late 1990s, Guy’s sister-in-law, Jocelyn, courted

publicity from

New York magazine and

Vanity Fair during

a divorce from Alec; allegations emerged of Russian models, pet

leopards, five-figure laundry and dry-cleaning bills, and Jocelyn’s

disfiguring facial surgery, which was, according to Alec, her ongoing

attempt to look more like a cat.

“We have always been very

discreet people,” Wildenstein told the French magazine. “My father was

not worldly, I am not, to the point that almost no one knows what my

wife looks like.” (Worldly, of course, is different from global;

Wildenstein is a French citizen, born in New York, who educated his

children at the Lycée Français on Manhattan’s Upper East Side and Ivy

League schools.) He was so down to earth, Wildenstein claimed, that

despite being president of the family business, Wildenstein & Co.,

since 1990, he was in no position to have hidden the family’s fortune

from the French government, as he’s charged with doing.

“My

brother and I were clueless,” he said. “My father never spoke of his

business. He would not come to ask me for advice to manage his fortune

or dispose of his property while he was alive. I knew he had the trusts,

but he never informed me of detail.” Through a lawyer, Wildenstein

declined to comment for this article.

Daniel, left, and Alec at the New York Gallery in 1965

Photographer: AP Photo

In

1870, Nathan, the founder of the Wildenstein dynasty, left his native

Alsace for Paris, where he soon switched professions from hemming pants

to hawking paintings and opened his first gallery, on the Rue Laffitte.

The art world was in transition: For centuries, the only people who

bought and sold oil paintings of any quality were the aristocracy of

Europe; there were marriages to arrange, mistresses to flatter, and

châteaux and castles to fill with whimsical landscapes and frolicking

nymphs. But by the end of the 19th century, that same aristocracy was at

the tail end of a 200-year-long decline, ground down by industrial and

political revolutions.

The old world’s demise coincided with the

rise of the new: Flush with almost unimaginable wealth, American

millionaires like the Rockefellers, Fricks, and Guggenheims were eager

to buy what the old aristocracy was desperate to sell. Nathan, and then

his son, Georges, became the middlemen, arriving cash-in-hand to empty

châteaux of masterpieces and then, in turn, sell them. For the best of

these works, the next step was inevitably for them to end up in the

great museums of the U.S.

Take, for example, Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s

The Two Sisters,

a lively portrait of two elegantly dressed young women currently on

view in Gallery 615 of the Met. First in the possession of the Marquis

de Veri, a prolific French art collector, it bounced to another marquis,

then to a collection in Sweden, next to the consul general of Russia,

and then, in 1916, to the Wildensteins. Their gallery held on to it for

two years and then sold it for $194,000 to American coal-mining magnate

Edward Berwind, whose family later gave it to the Met. It was just one

of many. Berwind, for one, bought another picture, by Marie-Guillemine

Benoist, from the Wildensteins that year for $228,000.

In 1903 the

Wildensteins opened a satellite gallery in New York; in 1905 they moved

their Paris gallery to 57 Rue La Boétie, an ornate mansion designed by

Charles de Wailly, who also designed the Paris Odéon. By 1925 there was a

Wildenstein gallery in London, and the family was selling artworks for

several thousand times the average U.S. annual income. In 1915 they

bought the Château de Marienthal, one of the largest private houses in

Paris; a few decades later they moved their New York gallery to a

five-story mansion on East 64th Street, then bought another mansion a

few doors down as the family residence.

Daniel,

Georges’s son and sole leader of the third generation, was on course to

transform the gallery and his family from mere dealers into towering

experts in the field. Based for most of his life in Paris (though the

private jet, with the family’s insignia of three blue horseshoes on its

tail, made continent hopping easy), Daniel fashioned himself as a

gentleman-scholar, establishing the Wildenstein Institute in Paris. The

institute’s signature was its catalogues raisonnés. Its Monet catalog

took 40 years to assemble; its Edouard Vuillard, 60 years. Work of this

sort heightened the gallery’s status even further. “I think it was when

you were super rich and wanted to show off, you’d go to Wildenstein’s,”

says Richardson, who is best known for his multivolume biography of

Picasso. “You could tell everyone back in Chicago, ‘Oh, I was in

Wildenstein’s the other day. I’m thinking of buying a Raphael.’”

Daniel, center, with his second wife Sylvia, and Guy in 1984

Photographer: Alan Davidson/The Picture Library

In

many ways, the Wildensteins’ influence peaked in 1990, the year Guy

became president at Wildenstein & Co. and unveiled the Caravaggio

that would end up on the Met wall. Long thought to be a copy, the

painting was an old master, according to Keith Christiansen, then

curator of European paintings at the Met. The news was rolled out with a

50-page catalog and a Met exhibition, A Caravaggio Rediscovered:

The Lute Player. A

New York Times review called the painting’s authenticity

irrefutableand noted that the work had been placed on “long-term loan” at the museum.

Left unsaid was the windfall for the Wildensteins.

The Lute Player’s

newfound status shifted its estimated value from thousands of dollars

to somewhere just shy of priceless. Lists of the most valuable paintings

in private hands put its current value at up to $100 million, though

the dearth of top-level Caravaggios at auction means assessing its true

price is impossible. All of this speculation would be academic—the

painting was on loan to a museum, after all—if the Wildensteins hadn’t

almost immediately borrowed against the work’s value. While the

Caravaggio appreciated in the Met, the family invested the painting’s

value as it saw fit.

Yet just as Guy, then already 55 years old,

was finally easing into the leadership of his father’s business, the

business changed. “Now the big money is largely in modernist art,”

Richardson says. “And the old master department side of the business,

which was their main thing, is not doing at all well.” By the late 1990s

the family began to fragment, and its art dealing, at least publicly,

began to subside. They were less in the art business than in the

being-rich business. And then the Wildenstein women turned the tables.

Jocelyn on the cover of

New York magazine in 1997

Judging

by his reaction, Alec wasn’t expecting his wife to return home on the

night of Sept. 3, 1997. Jocelyn had been safely far away at the

75,000-acre Wildenstein

ranch in Kenya (the one with the elephants and white rhinos, where

Out of Africa was

filmed). Arriving at their Manhattan town house, she found 57-year-old

Alec with a 19-year-old woman. Alec, furious at the intrusion,

brandished a semiautomatic pistol while holding a towel around his

waist. Jocelyn called the police, and Alec spent the night in jail. The

ensuing divorce, played out in the New York tabloids, was just a preview

of how the family’s finances would be exposed following the patriarch’s

death

four years later.

In

October 2001, Daniel, who had battled cancer, fell into a coma. His

second wife, Sylvia, sat vigil by his hospital bed until his death on

Oct. 23.

Two weeks later,

she signed away her rights to her late husband’s estate. According to

Sylvia, her stepsons—Guy and Alec—had told her the taxes would bankrupt

her if she didn’t. It wasn’t until

two years later

that she hired a lawyer. She eventually filed a lawsuit against Guy and

Alec claiming, among other things, that she was bilked out of her

inheritance and that the family was sitting on trusts and real estate

worth not millions of dollars, but several billion.

The French tax

authorities took notice and began looking more closely at Daniel’s

estate—and came to believe that they, too, got lowballed.

As

French prosecutors would later learn, simultaneous to the Wildensteins’

claim in court that Daniel’s estate was worth no more than $45 million,

the family’s representatives were negotiating to borrow $100 million

using $250 million worth of art as collateral, according to

correspondence on the deal from a Cayman Islands unit of Coutts &

Co., known as the Queen’s bank because Elizabeth II is a client. The

proposal called for the Wildensteins’ Delta Trust to pledge a mix of

pieces by artists from diverse periods. (The works in the trust

included, in addition to paintings from Pierre Bonnard and Fragonard, a

Picasso sketch of Guy and Alec’s grandmother, Madame Georges

Wildenstein, from 1918.) In exchange, Coutts would supply the cash and

invest it on behalf of the Delta Trust. The deal wasn’t completed,

according to a person familiar with the negotiations.

In 2005 the

Paris appeals court voided the inheritance agreement Sylvia had signed

and ordered a full inventory of the family’s properties, ranging from

homes in New York and France to the Kenyan ranch, trusts, racehorses,

and art. Amid the upheaval, Alec died in 2008. Sylvia died next, in

2010. That left Guy, known as the more diligent brother—he dutifully

showed up to work at the New York gallery every day and, perhaps just as

important, never made headlines for marital infidelities—to bear the

full brunt of the French government’s investigation.

The French

fiscal authorities notified the remaining Wildenstein heirs in 2011 that

their audit had found taxable assets totaling €615.7 million—more than

10 times what the family originally declared. That tally included 19

Bonnard paintings valued at €64.9 million that had been stored at the

Geneva Free Ports & Warehouses (held in a trust named after Sylvia)

and €281.3 million of paintings held by the Delta Trust. Yet even this

figure is modest compared with what the tax authorities would ultimately

produce. The Delta Trust alone, they now say, has a value of $1.1

billion.

This time around, the tax bill won’t be covered by the donation of bas-reliefs. The French government issued a

proposition de rectification that

demanded an additional levy of €469.4 million, including interest and

penalties. Later the figure was lowered to about €448 million.

On

April 9, 2015, investigative judges in Paris indicted Guy and other

defendants, including Alec’s widow (he had remarried) and son and

several advisers to the family, on charges related to the handling of

Daniel’s estate. Along with the $188 million art airlift, investigators

claimed a further $850 million worth of paintings inside the trust were

dispersed around the world, with most in Switzerland and bits scattered

in Paris, London, Buenos Aires, Tokyo, and other cities, the indictment

says.

The Wildensteins, who maintain the validity of their

original tax claim, asserted in court that the assets held in trusts

weren’t legally Daniel’s to take at will. Instead, they belonged to the

trusts and therefore shouldn’t count for estate taxes. Prosecutors

countered that the trusts aren’t truly independent, pointing to evidence

that the Delta Trust became a source of bounty for Guy and Alec, to

whom dozens of artworks totaling tens of millions in value were

distributed from 2001 through 2004. It’s preposterous, prosecutors

asserted, to claim that no one actually owned paintings worth hundreds

of millions of dollars.

Dozens

of major assets still have escaped full scrutiny, and they will at

least until the French authorities—who can levy estate taxes on assets

held anywhere—have fully worked out who owns what. New York properties,

including the Wildenstein & Co. headquarters, for instance, which

the family came close to selling to the Qatari government for $90

million in 2014 (Qatar pulled out), private jets, and even the

Caravaggio, don’t factor into France’s tax claims. There’s also no

mention of stocks, bonds, or cash. The full extent of the Wildensteins’

wealth is unknown. But there is a very public record of the transactions

behind the family’s fortune—and its reputation. You just need to look

on the walls of the world’s greatest museums.

Millions of visitors to the Art Institute of Chicago have admired Gustave Caillebotte’s

Paris Street; Rainy Day, from 1877, one of the most famous paintings of the 19th century. The Wildensteins sold it to the Art Institute in 1964.

The

Met has its own list of masterpieces connected to the family. Walk up

the grand main staircase, and you’ll come to the entrance of the immense

European Paintings galleries, a labyrinth of rooms with dark oil

paintings in heavy gilded frames. Close to half of the section’s 44

galleries have at least one painting with Wildenstein provenance;

Gallery 615 alone has seven that were once owned by the family.

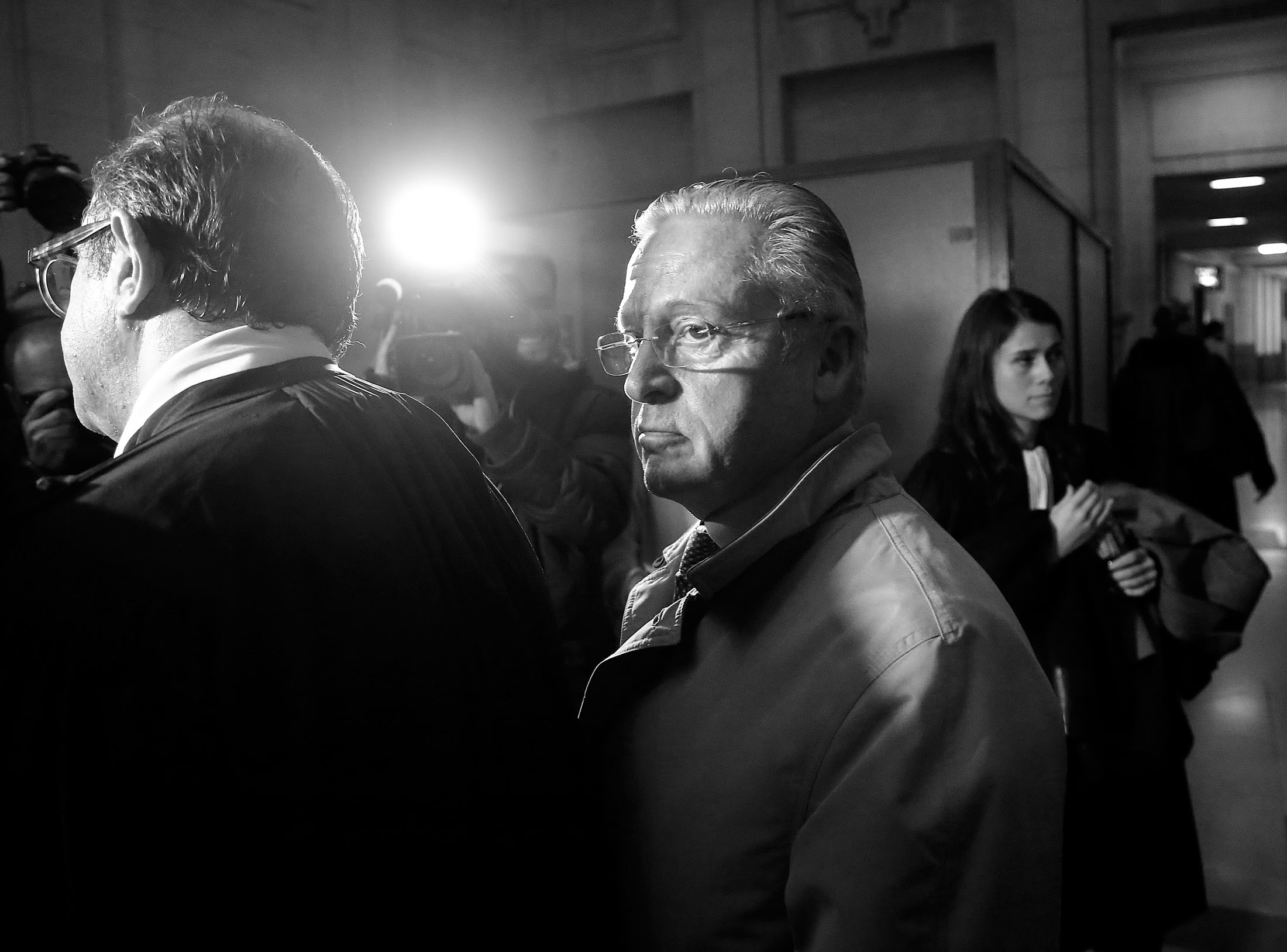

Guy with his lawyer in January 2016

Photographer: Michel Euler/AP Photo

Wildenstein

art at the Met isn’t just old masters. When Walter Annenberg, the

publishing billionaire, donated 50 impressionist paintings to the museum

in 1991, the

New York Times estimated their total value to be

“roughly $1 billion.” Twenty-seven of the 50 were purchased from the

Wildensteins or passed through their hands, including a stunning

green-and-white still life,

Roses, by Vincent van Gogh.

All

told, at least 360 objects in the Met have a Wildenstein provenance.

They include oil paintings, drawings, watercolors, sculptures,

tapestries, and even gilded mirrors. Taken alone, they would constitute a

world-class museum.

One work, however, would be missing from this hypothetical mini-Metropolitan: In 2013 the Wildensteins quietly removed

The Lute Player from

the Met’s walls. The long-term loan had been terminated. Outsiders

speculated that with Daniel and Alec dead, the heirs besieged by

lawsuits, and the art-dealing business a shadow of its former self, the

prestige of having a $100 million painting hanging in a museum had

ceased to outweigh the security of having a $100 million painting in the

family vault. Where that vault might be, exactly, is a matter of

speculation.

—

With Gaspard Sebag

Burne-Jones painting stolen from a cottage in West Sussex

A

painting by Edward Burne-Jones was among the items taken in two

burglaries at the same property in Linchmere, near Haslemere last month.

Hope in Prison by Edward Burne-Jones which was stolen from a house in Linchmere, near Haslemere.

Thieves struck first at the secluded cottage between

June 3-8, taking a version of Burne-Jones’

Hope in Prison out of its frame. Dating from 1862, the work is valued at ‘tens of thousands of pounds’, according to police.

In the second theft, 40 pieces of silver cutlery and two silver candlesticks were taken.

The incident took place between June 17-20.

Det

Con Pippa Hannard of West Sussex police said they want to trace a blue

people carrier – possibly a Vauxhall Zafira or similar – seen in the

area on

June 11-12.

Anyone

with information is asked to phone 101, quoting serial 797 of 08/06

concerning the painting theft and 813 of 20/06 concerning the silver

theft.

Sources: The Met/Art Resource (5); The Art Institute of Chicago/Bridgeman Library

Sources: The Met/Art Resource (5); The Art Institute of Chicago/Bridgeman Library

Hope in Prison by Edward Burne-Jones which was stolen from a house in Linchmere, near Haslemere.

Hope in Prison by Edward Burne-Jones which was stolen from a house in Linchmere, near Haslemere.